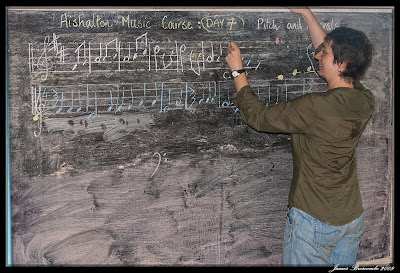

Working on rhythm by singing with actions

Retention has been good, and the quality of attention astounding.

Agnes and Joan taking down the notation for today's new song

Sister Lucy and Clara, our dancing stars!

Adults are giving up time on their farms to be here, children stacking up home responsibilities for the weekends. I’m trying to imagine some of my sister’s London pupils coming early to music class to sweep the dead cockroaches, storm dust and general detritus out of a large hall, without being asked. Failing. We have learnt all the basics of musical notation and are now starting to apply some of it. We’re grappling with the idea that there are choices to be made in singing- even dynamics have come as a shock, so phrasing is positively Copernican.

The most intriguing thing to me has been trying to imagine a world where songs are organic mysteries. Why should you expect a song to be fathomable, and to sound the same every time, if you’re thinking of it as a tree or a small fruit bat? I am trying to appreciate “To God be the Glory” with anything from 4 to 9 beats in the bar, but it definitely feels unsatisfactory; refractory, like a bad-tempered camel. Because people on the course have expressed some frustration with the rhythmic incontinence of Aishalton’s musical style, I am trying to teach them about songs as buildings: deliberately constructed, balanced and often even symmetrical constructs, containing rooms with different functions. I hope I haven’t killed anything in the process. Of course, some songs can carry off a certain time-signature fluidity- and others can’t get any worse. We have some amazing Caribbean choruses that certainly make it easier to imagine WHY people think of songs as trees or small fruit bats.

Closing celebration (Father Britt centre)- clapping 5 concurrent rhythmic patterns

We finished the course today with a concert party for friends and family. Everything was home-made: the programme, giant notes frieze, music education posters, doughnuts and cake and cool-down (Rupununi name for flavoured drinks). The participants conducted, danced, clapped, sang, acted and laughed their hearts out. The audience, of an even wider age range than the participants (5-90, to be precise), joined in with the clapping and dancing. It was a wonderful afternoon. I can’t tell you how proud I am of them. They are clearly proud of themselves and each other too. I don’t know whether anything will come of the course, or whether participants will consolidate what they have learnt. But ‘development work’ could get terribly humourless and ethicatious if I’m not careful. Sometimes we all need a bit of extravagance, a bit of beauty and a bit of nonsense. Music is a great place for the childish and the childlike to meet, and replace inhibitions with exhibitionists. It’s a friendship centrifuge.

the shadow says it all...

Joining the hordes to eat outside during the Celebration in May