I’m leaving Guyana today. Saying goodbye to Georgetown the gorgeous garbage-garden city, Guyana the land of many waters, and Aishalton the visceral laborious beautiful home. Forgive the plethora of adjectives; they are hard to avoid in a place of such extravagance. My outsider’s impressions were of course never more than that- impressionistic, partial, leaving not much more behind than an aura, a little smoke, a whiff of mangoes or gunpowder. But if you never get the chance to come to Guyana, perhaps these words have carried enough of an aura, enough of a glimpse through a dark glass, to bias your heart a little when you hear the cricket scores, snag your attention when some Amerindians protest their land rights in Brussels, or trigger a vibration when you hear a frog belching its lovesong or catch livestock chewing your laundry. And if you have approached these outsider stories from the inside, thank you for your forbearance in allowing me such freedom to anecdotalise and compartmentalise your vivid world into two thin dimensions. I shall miss your generosity and your punchy plosive late-stressed words (‘charácter’, ‘grandfáther’, ‘vehéemently’) and your culturally intriguing responses.

As I look back over the projects and the newspapers, the politics and the alcoholism and fantastic trainees and spate of young deaths and sewing and singing and writing and planning and all these crazy vivid experiences, I am very struck by how jam-packed our world is with love and hope, chaos and despair. True for Guyana, true for anywhere. We choose by our attentions which we believe matters most. We make our choices by default gradually as we settle into adulthood, and equally gradually as our life goes on the choices begin to make us. As we absorb ourselves in love, or hope, or chaos, or despair, so we are absorbed by them. I am sure I would have assented to this a few years ago, but I’m not sure I knew how to live by it. (I’m not sure I do now).

In his novel ‘The Eighth Day’, Thornton Wilder’s feistiest woman says: “Cities come and go... like the sand castles that children build upon the shore. The human race gets no better. Mankind is vicious, slothful, quarrelsome and self-centred. If I were younger, and you were a free man, we could do something here- here and there. You and I have a certain quality that is rare as teeth in a hen. We work. And we forget ourselves in our work. Most people think they work: they can kill themselves with their diligence. They think they’re building Athens, but they’re only shining their own shoes. When I was young I used to be astonished at how little progress was made in the world... From time to time everyone goes into an ecstasy about the glorious advance of civilisation- the miracle of vaccination, the wonders of the railroad. But the excitement dies down and there we are again- wolves and hyenas, wolves and peacocks... Everything’s hopeless, but we are the slaves of hope”.

I am uncomfortably aware that some of the stories I have told you have been distressing, and a few were downright disheartened. Development work is a minefield, littered with sloppy good intentions, bossy interventions and the exploded limbs of a thousand insane outsiders’ crazy projects. Desolation is sometimes inevitable, but other times it’s just lazy. Hope, on the other hand, is an extremely demanding path to follow. I look back over our time here in some awe at all that has happened to us. I’m glad we weren’t only shining our own shoes (shiny? Hmmm!- pungent, more like...). I particularly marvel at how many profoundly worthwhile people actually shared themselves with us in some significant way.

Despite the real insights in Thornton Wilder’s words, I do not believe that the conclusion he draws is right. Seems to me there are a lot more creatures out there than wolves, hyenas and peacocks. We are not slaves of hope, though we may choose to be its servants. In his “Last Essays”, Georges Bernanos wrote “Hope is a risk that must be run”. I cannot put it better than that. I think what he means is something like this- do not sleepwalk your way unbeknownst into a future that chooses you as victim of its whim. Risk everything. Spend time like the wisely rich spend money. Spend it on something valuable, somewhere unforgettable, with people who matter to you.

Thank you for reading.

With love,

Sarah

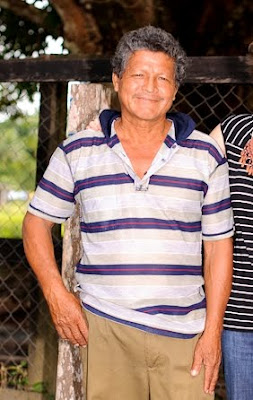

There is a quietness in his face that would be easy to mistake for gentleness. I don’t think it is. I think it is peace. I think that he has chosen a life in which there are no ambitions, and few nagging worries, tugs of loyalty or twisted feelings, and is enjoying the fruit of that choice without vanity and without drama. Eustace is one of the most impressive men I have ever met, but I suspect he would be astonished and baffled to hear that, and I’m not sure it would be welcome. He neither knows nor cares whether he impresses. That is the taproot of his dignity.

There is a quietness in his face that would be easy to mistake for gentleness. I don’t think it is. I think it is peace. I think that he has chosen a life in which there are no ambitions, and few nagging worries, tugs of loyalty or twisted feelings, and is enjoying the fruit of that choice without vanity and without drama. Eustace is one of the most impressive men I have ever met, but I suspect he would be astonished and baffled to hear that, and I’m not sure it would be welcome. He neither knows nor cares whether he impresses. That is the taproot of his dignity.